Location and Context

Geography

St. Monica’s original premises was situated right in the centre of the city on one of main thoroughfares between the City Bowl and the Cape Town docks. Although this area has become increasingly gentrified, it was once one of the city’s poorest and most overcrowded locales with well-to-do residents preferring to live in the leafy Southern Suburbs throughout much of the twentieth century. Surrounded by the largely working-class suburbs of District Six, Zonnebloem, Woodstock and Salt River, St. Monica’s was well positioned to serve these communities.

The new premises, built in the late 1940’s, was less than 400m away in the predominantly Muslim suburb of Schotse Kloof. The area borders Signal Hill, one of the places in Cape Town where people without housing were able to build temporary shelters away from the view of the municipality.

The maps below show where the old (left) and new (right) St. Monica’s were located but they reflect the city as it is now and not as it was when the premises were first erected. For an interactive website with six sets of topographic maps of Cape Town and surrounds covering the period from 1940 to 2010 click here.

Living Conditions

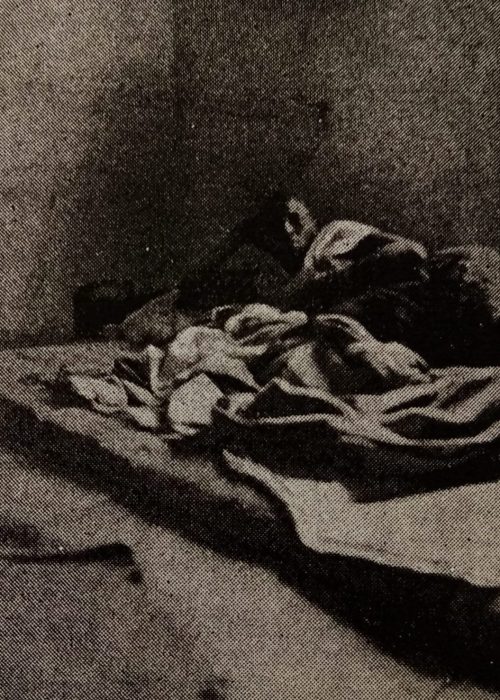

During the 1920’s and 1930’s Cape Town underwent a severe housing crisis as a result of which many families were forced to accept subpar housing, with absentee landlords in District Six and the City Bowl increasing their profits by squeezing more and more people into poorly maintained properties with limited facilities. Reports from St Monica’s contain vivid illustrations of the circumstances in which many of the Home’s coloured and African patients lived.That housing conditions were appalling, particularly in District Six, was repeatedly emphasised, with a typical district room being described thus:

“Size about 4 ½ ft., x 14ft. A low sloping roof, 6ft., to 8ft. high, in bad condition with many leakages. Plaster walls in bad state of repair, and not weatherproof. Flooring so rotten as to be unsafe in many places. The shutter, which partly covered the aperture where a window should have been, was part of an old stable door and quite inadequate to serve the purpose intended. The room was lighted usually by one small fixed window, 2ft., by 2ft.”

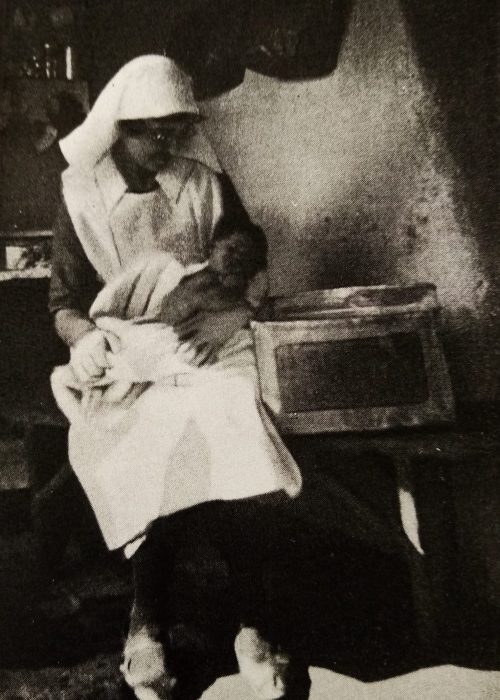

In 1944 St. Monica’s took the difficult decision to black list certain dwellings that were felt too dangerous for midwives to go into, even in response to emergency calls. Nonetheless, St. Monica’s midwives continued to be dismayed by the degree of squalor and deprivation which they encountered.It was not uncommon for a woman to be found lying on the bare ground, giving birth in full view of her neighbours, nor was it unusual for a newborn baby to be clothed using only scraps of newspaper. St. Monica’s staff made it their mission to provide assistance in such circumstances.

Click here to see a 3D model of the kind of home commonly seen in the poorer areas of Cape Town.

Mixed Motivations

The relationship between the St. Monica’s staff and the communities which they served was generally positive, with the fact that they were willing to assist expectant mothers in their own homes free of charge endeared them to even the most reluctant of families. However, concern for the plight of young mothers within these communities was not St. Monica’s only motivation for fostering such congenial relationships. Rather, the home formed part of a larger mission network, the aim of which was to prevent an increasing section of Cape Town’s working class population from adopting Islam.

For a variety of reasons, including but not limited to religious beliefs on the value of charity, economic considerations and a desire for fresh converts, the Muslim community in Cape Town proved willing to receive into their homes pregnant women unable to seek assistance or undergo their confinement elsewhere. In areas like District six, where racial as well as religious boundaries remained fluid, inter-religious marriages were also relatively common, especially in instances where a premarital pregnancy had occurred .

Within this context St. Monica’s formed part of a larger mission network the aim of which was to prevent an increasing section of Cape Town’s working class population, and particularly expectant mothers, from converting to Islam. To quote Archdeacon Lavis, one of the founders of St. Monica’s Home and Chairman of its committee:

“St. Monica’s is a very real part of the Mohammedan Mission Work in the Cape, particularly [as regards] young and misled mothers with their tiny infants […].Whether the father of the tiny babe is a Moslem or not is not of such great importance but what is of great importance is the fact that the next step prompted by the Tempter to the already erring one, is to hide what is shame in the eyes of her Christian friends under a cloak of seeming respectability – in a Moslem household, an easily opening door resulting almost inevitably in the forsaking of her Christian Faith.”

Claims such as this angered the Muslim community which felt that such accounts amounted to a deliberate perversion of the facts; a lengthy debate ensued throughout the second quarter of 20th century. Prominent politicians and spokespeople from within the Muslim community like Cissie Gool also expressed their frustration at St. Monica’s refusal to allow non-Christian’s to train as midwives (see article below).